Ryan Drum

Island Herbs

P O Box 25, Waldron, WA 98297-0025

About Ryan | Articles | Contact Ryan

TWO BUDS AND A LEAF: Poplar Buds, Grindelia Buds and Fig Leaves

MEDICINES FROM THE EARTH 2008

These three readily available herbs contain non-water-soluble therapeutic substances: dense resins in Populus spp., viscous gums in Grindelia spp. and latex in Ficus spp. leaves and fruit buds.

POPLAR

BUDS

POPLAR

BUDS

Also known as Balm of Gilead Buds, these buds have a long history of

medicinal use (Grieve, Osol).

The poplar buds used to make Balm of Gilead extracts are usually from Cottonwood Poplars; the most effective medicines are made from the extremely aromatic and resinous dormant leaf and floral buds of the cottonwood poplar, Populus trichocarpa. Other western poplars such as the balsam poplar common in the Rocky Mountains and the arid plains of Alberta also have ample amounts of extractable resins. The poplars with the least amount of medicinal resins are the Lombardi poplars and the various hybrid poplars grown for paper pulp.

Poplar buds are best used fresh, live for medicine. If not fresh, then frozen and thawed. Freeze-dried buds may produce effective medicine, I do not know. Dried buds will always be rotten, black and crumbly inside from fungal decay. The drying process takes 3-6 weeks. The very same resins that protect the magnificent buds from rotting and freezing on the tree, also impede rapid or even effective drying at 70-100° F. I have only dried them twice and both times the buds rotted within before complete drying obtained. When I went out into the herbal marketplace, I saw that all of the dried poplar buds available were also rotten within. DO NOT USE DRIED POPLAR BUDS FOR MEDICINES.

HARVESTING POPLAR BUDS

The closed dormant buds can be harvested anytime after they are fully formed, often by Bastille Day ( 14.July) right on thru the late summer, autumn, and winter. When the late winter or early spring temperatures rise above about 52-54° F for the most of daytime for several days, the buds rapidly burst open, flinging aromatic bud scales onto the ground and displaying beautiful reddish catkins for the bees to pollinate, and they do with gusto.

Once the buds begin to swell immediately prior to opening, it is probably too late for medicinal harvesting. I believe the best time frame for gathering poplar buds for medicine is in Capricorn and Aquarius, circa 20.December thru 22.February. I have picked the buds from intact live trees, from just felled trees, and from windfall branches blown down during major windstorms. I much prefer the latter.

As soon as the weather clears after a big wind storm in late December or early January, and the temperature is 28-35° F, I go out well-dressed into the swamplands with a 1-2 gallon hard plastic bucket and leisurely pick from one-half to one pound an hour of live buds. I harvest both the terminal buds of fruiting spurs and the lateral buds originally formed as axillary buds; when the entire tip of a fruiting spur is covered with a thick resin coating, so that the stem as well as the terminal bud and the subtending 2-7 leaf buds are reddish-brown, I carefully snap off the entire resin-coated twig and include it. I check carefully the butts of every bud and stem to make sure they are green and white, with no black or brown lines; such dark lines always indicate that fungal rot has already begun within the bud, either when the branch was still on the tree, or, that the branch has been off the tree for too long, probably from an earlier storm. Temperatures colder than 28° F are too cold for bare fingertip harvest. Warmer temperatures present buds which are very sticky. The warmer the temperature, the stickier the protective bud resins become, as well as the harvester's fingers and/or gloves, which become so unmanageably covered with sticky resins that everything sticks to the fingers, including the just-picked buds.

I try to use only one particular hand during each harvest session, to retain a non-sticky useful hand for other functions. Due to considerations of cold and daylight, I usually only harvest 3-4 pounds per harvest session. Since I live within walking distances of the trees, I do not need to worry about being able to drive or about getting a good return for my travel time and capital invested in a vehicle, etc. A drive-in harvest would need considerably more efficiency to actually be profitable.

If the buds are picked too quickly, pre-harvest rotters are likely to be unnoticed and unfortunately included with the harvest. These often swollen, brighter green buds are very plump and big, but have characteristic partially-opened outer scales, indicating damage by trauma or fungal rot within. These rotters will contaminate the other buds and increase the likelihood of further buds rotting as well as the macerating buds once in oil.

For the best medicine, the buds should be placed in the macerating medium as they are picked. Often this is too difficult in the cold and on foot. The next best procedure is to have the menstruum ready before the buds are harvested; otherwise, keep the buds chilled until ready to use; if this will be a long time, consider freezing them. Having lived without refrigeration for 30 years, freezing was not a real option for me. I have no direct experience, only hearsay from other healers.

PROCESSING POPLAR BUDS FOR MEDICINE

EQUIPMENT ALERT: Jars, pans, and other poplar bud processing equipment will tend to become coated with resin deposits. I dedicate certain equipment to processing poplar buds. The insides of teapots used for poplar bud tea become poplar bud and resin-coated; I use a heat-resistant canning jar to steep poplar buds for tea.

Poplar buds have a relatively small amount of water in them. They are so dense they will sink in water. They are suitable for hot oil maceration without any mechanical preparation. Do not mash, cut or otherwise mechanically damage the buds before putting them in the macerating oil; ESPECIALLY, do not blend the fresh buds with oil.

POPLAR BUD OIL:

Poplar bud oil is simply made by placing one part of poplar buds (live fresh poplar buds) into three parts appropriate oil: this means for 1 quart of maceration, use three cups of oil and one cup or 1/2 pound of fresh live poplar buds. I use olive oil, extra virgin organic.

For one gallon of macerate, use three quarts of oil and two pounds of fresh buds.

Add the cold buds directly to oil at room temperature (circa 70° F) into a glass or stainless steel maceration vessel. Do not put cold buds into hot oil. The warming together promotes gentle cell death and yields a superior medicine.

Stir buds in oil gently with a wooden spoon handle to mix the oil around the buds and to discharge any and all air pockets; air pockets promote decay and spoilage.

Heat the container with the macerate (mixed oil and buds) in a water bath or double-boiler to a constant 115-120° F, and maintain for at least 72 hours.

The functions of heating are to:

1. Raise the temperature of the resinous material binding the bud scales and coating the inner and outer surfaces within the buds sufficiently to allow the resin to become very fluid and speed up the dissolution of that resin , carotenoids, phospholipids and the phenolic salicylates of populin and salicin (Gilman, et al) by the oil as the bud scales loosen and partially separate.

2. Evaporate the water releasd by cell death from previously live bud cells. This water must be removed to prevent both decay during maceration and spoilage in the final product.

3. Drive out residual air pockets.

4. Kill topical bacteria and fungi. Air, water, and microbes all can lessen the effectivness and stability of the final oil product.

Stir the buds in the hot oil four to eight times daily during those first 72 hours (three days) to hasten air and water removal.

After 72 hours or so, (the exact timing is not critical; but doing it the same way each time will tend to yield more consistent product quality and effectiveness) keep the buds and oil macerating together at 90-105° F for at least 2 weeks, a month is better. Oil extraction speed and efficiency of resinous materials is very temperature dependent; higher temperatures tend to promote better extraction; conversely, I believe even slighty too high temperatures can accelerate molecular fragmentation and degradation, often losing important healing constituents, particularly components of populin and salicin.

During the long maceration, try to stir the buds gently at least once daily with a wooden spoon handle or other suitable wooden implement. Except when stirring, keep maceration vessel LOOSELY covered.

After one month, let the oil and buds stand for 48 hours without stirring; then very carefully pour the oil off the buds (decanting) into a clean dry clear glass container; wash this container and dry totally before using; the object is to eliminate water from the final product. To help facilitate this, let the decanted oil in the clear glass container stand for 48 hours, covered, at room temperature ( about 70° F). After 48 hours, very carefully examine the material, if any, at the bottom of the oil in the clear container, to look for little water droplets; hopefully, there will be none. If any, carefully decant the oil into another clear clean jar, trying to leave any water droplets behind. The water-free oil is ready to use, store, blend.

Poplar bud oil extracts are usually very rich in anti-oxidants. These extracts tend to not go rancid, often for a decade or more. Historically and probably prehistorically, indigenes in the Mexican northwest and the American Southwest, used whole cottonwood poplar buds directly in oils, and animal fats and greases to prevent rancidity. I have personally preserved lard for over five years at a time in this manner. This means that poplar bud oil products can have a long shelf life, especially if carefully stored in airtight containers. I always store those products in glass containers and not plastic to avoid the leaching of endocrine-disruptive plasticizers into the poplar bud extracts.

DO NOT PRESS THE BUDS LEFT IN THE MACERATION JAR IN AN ATTEMPT TO CONSERVE OIL.

IF YOU INSIST ON PRESSING THESE SEMI-SPENT BUDS, PLEASE DO NOT MIX THE OIL FROM THEM WITH THE CAREFULLY-DECANTED WATER-FREE OIL.

Instead, set up a second maceration with the original buds: add the oil-soaked buds to an equal amount of fresh oil at room temperature, heat to 120-130° F for 12-24 hours, stirring frequently. Thereafter, keep in a warm place, about 100° F, until ready to process:

1. Pour off the oil and keep in a separate container.

2. Press the buds firmly to squeeze out most of the oil; keep this separate from the decanted oil in step 1. Use as a massage oil

OR 3. Leave oil and buds in the second maceration together until the oil is used. Infused poplar bud oil which has not been poured off the settled resins seems to yield better and apparently increasingly more powerful medicine: sometimes for years. Such longterm storage must be moisture-free and preferably stored in the dark. It may eventually rancidify.

A fascinating complicating factor in the preparation of poplar bud oil extracts is the complex nature of the protective resins; in most buds, there are several different resins of varying solubility in the macerating oil. As the maceration progresses, one or more different resins may deposit on the sides of the maceration vessel or as discrete separate layers on the vessel bottom. These resins are the same ones that bees use to maufacture propolis, the antimicrobial plaster for their hives. (See below) Much of the healing action of poplar bud extracts seems to be dependent upon the amount of resins dissolved into them. (Similarly, much of the therapeutic healing value of poplar bud oil and alcohol extracts derives from the phenolic salicylates in populin and salicin.)

POPLAR BUD TINCTURE

I tincture fresh poplar buds in 50-70% aqueous ethanol, 1 part buds to 3 parts alcohol, in closed glass containers at 90-120° F for 72-96 hours, with frequent shaking of the container, and then store the tincture with the buds, decanting off as needed.

Curious, I tried alcohol extraction of previously oil-extracted poplar buds with messy unusable results. Similarly, oil extraction of previously alcoholic-extracted poplar buds yielded waste only.

POPLAR BUD TEA

For poplar bud tea, I simmer 4 oz fresh buds in 16 oz water for 5-10 minutes and steep until cool enough to drink. Often I leave the buds in the pan and add another 12 oz water and bring to a boil again and then steep until cool enough to drink.

PROPOLIS

Bees gather the antimicrobial poplar bud-sealing resins to make propolis. They use propolis for shaping the interiors of hives and to seal intruders (such as mice) in the resin to prevent decay and protect the hive (Pojar & Mackinnon).

Propolis has a long and revered healing tradition from the ancient Greeks through the present. I believe the healing properties of propolis are mainly from the resins and salicylates of early spring poplar buds. I use oil and alcohol poplar bud extracts and salves for all uses recommended for propolis.

MEDICINAL USES OF POPLAR BUD EXTRACTS

NOTE: The medicinal properties and efficacy of poplar bud extracts can vary greatly according to not only the species used, but even the individual trees used, the time of the year harvested, how the buds are harvested, and how they are processed into medicine.

CAUTION!! WARNING!! Another complicating factor is that a small, probably less than 1% of the American population seems to have an exaggerated epidermal sensitivity to the poplar bud resin or juice and they develop the early signs of anaphylactic shock; flushed face, labored breathing, hives (often very itchy), swollen face, itchy runny eyes, and some dizzyness. Most of these people have general sensitivity to aspirin and aspirin products. Poplar buds contain populin and salicin, phenolic glycosides, both contain salicylates. Use caution or provide some warning. Salicylic acid is so irritating it can only be used externally.

Some small herbal product producers do not use poplar bud extracts because of potential harm to anonymous users of their products.

Salicylates are extremely useful as mild pain relievers; they alleviate pain by virtue of both a peripheral and CNS effect. Our bodies do not seem to develop a tolerance for salicylates, so that increasing doses are not necessary for the same desired effects with continued use. (Goodman and Gilman).

In addition, due to the anti-clotting effects of salicylates, discontinue use of poplar bud extracts (oils, tinctures, teas) 10 days before and after elective surgery and after severe physical trauma.

POPLAR BUD OIL/SALVES

Poplar bud oil is a wonderful addition to massage oils, especially those used for deep tissuework. It is a superior first aid rapid response topical applied to scalds and burns. Poplar bud oil is antiseptic, speeds healing and lessons scarring. I use a 1:1 mixture of poplar bud oil and fresh St. John’s Wort floral bud oil as our household burn oil. The Hypericum oil is mildly analgesic and stimulates nerve regeneration at burn sites. Michael Moore (1993) recommends using animal fat (butter, lard) for poplar bud burn oil. I suspect a 1:1 mixture of sheep or goose fat can also be used. He recommends burn oil/salve for hemorrhoids: lessens pain, keeps surfaces clean and antiseptic, and stimulates nerve regeneration. Poplar bud salves have long been used externally on hemorrhoids.

Poplar bud salves and tinctures are applied externally for sprains, hyperextensions, and arthritic joints.

LAXATIVE USE OF POPLAR BUD OIL:

30 years ago at one of the legendary Dominion Herbal College 2-week summer seminars, where I was teaching, a married couple gave a marvelous workshop on Iridology (the reading of a person’s iris diaphragm for information about one’s health status ). Many of us were read to be constipated with obvious “bowel pockets”. The recommended treatment was 1-2 tablespoons of poplar bud oil every morning until cured. This may be a bit extreme.

Poplar Bud Tinctures are used internally for sore throats, headaches, sore muscles and joints (externally for sore body parts as well).

Poplar bud tea is anti-inflammatory, pain relieving, and relief for gout symptoms. I find it a more effective pain reliever than willow bark Tx. Modest internal use is recommended by me to reduce potential for gastric ulceration. Don’t drink poplar bud tea on an empty stomach.

COAST SALISH USE OF POPLAR BUDS

The Salish used poplar bud tea to calm the bereaved and for “opaque illness”. They observed that too much decocted poplar bud tea could be fatal.

Poplar buds were boiled in deer fat to make salve for sunburn, sores, and as a topical for rheumatism and body pains, and as a hair and scalp tonic. This salve was molded in hollow Bullwhip Kelp floats (bulbs). (Turner et al).

ETHNOBOTANICAL NOTE

In the Tibetan refugee marketplace in Pokara, Nepal, 1974, I purchased small bone vessels inlaid with little flat cut brass stars and circles. These brass inlays were glued to the bone surfaces with reddish poplar bud resin. I asked the seller about the glue and she pointed to a big poplar tree and I saw the familiar plump buds. The resin is totally water repellent.

Coast Salish in Washington and British Columbia mashed poplar buds in wooden tubs of water, using hot stones to heat the water to help separate the resins from the buds. The hydrophobic resins were used as woodworking glues and to help patch cedar log canoes, apparently very successfully for 5000 years.

REFERENCES:

Gilman,

A. et al 1980. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. Pp 688-698

Grieve, M.1931. Modern Herbal V.1; Pp 311-13

Moore, M. 1993. Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West. Pp52-55

Pojar, J. and MacKinnon, A. 1994. Plants of the Pacific NW Coast. Pp

46

Turner, N.J. 1992. Plants for All Seasons. Botany Class Compendium.

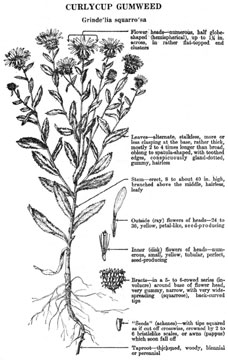

GRINDELIA BUDS (CURLY GUMWEED)

Grindelia

spp occur only in the western hemisphere. (The name of the genus honors the

Russian botanist, David Grindel.) This has resulted in a short but vigorous

history of therapeutic use by both European and Asian healing traditions.

Precontact use by natives was extensive. The flowers are extremely gummy and

covered with soft curly bracts handsome.

Grindelia

spp occur only in the western hemisphere. (The name of the genus honors the

Russian botanist, David Grindel.) This has resulted in a short but vigorous

history of therapeutic use by both European and Asian healing traditions.

Precontact use by natives was extensive. The flowers are extremely gummy and

covered with soft curly bracts handsome.

The Grindelias grow from Alaska to southern S. America. In North America, most species grow west of the Mississippi River, predominantly starting in the foothills and Front Range of the Rocky Mountains and west to the margins of the Pacific, where they grow to the water’s edge, out of steep sandbanks, and from soilless fissures in rocky cliffs. I have harvested them at 9000’ elevation west of Denver, Colorado; on mountain tops near Demming, New Mexico; and from dry arid hillsides of the central mountains of California and Mexico. In these drier habitats, the dessicated annual flowering stalks may persist for several years due to the preservative action of their gummy exudates. These relics often have a faint wonderful odor of vague incense.

The plants are frequently described as short-lived perennials. I have observed and harvested buds from the same relatively solitary seaside plants, growing out of sand berms, for over 30 years. Older Cliffside plants have hundreds of apical bud scale rings, and the perennial stalk is up to 1.5 inches in diameter and up to 6-8 in. emergent from the ground/sand/rock. I believe these plants may be hundreds of years old. When not in bloom, the plants may be all dried up or in moister habitats, display a lush green basal rosette of resinous leaves to 12 inches long..

Curiously, in one Italian herbal (Bianchini & Corbetta), Grindelia “…is indigenous to the SW United States, and likes wet marshy ground”. Exactly the opposite of my observations.

HARVESTING GRINDELIA BUDS

I hand-harvest grindelia buds bare-handed in a manner similar to how I pick blueberries: I cluster 4 or more individual buds between my fingers in an upswooping motion and pick them all at once. This means my fingers on the one hand I use become rapidly very sticky. Wet on the buds, the gum dries quickly on hands, ears, nostrils, car keys, money etc. I do not use tools to harvest Grindelia buds, they get too gummy and sticky. The sticky dried gum can be removed using old herbal salves. The buds of Grindelia Squarrosa develop and open from May through September, with the best buds available in Leo, mid-July thru mid-August. Some years, during prolonged flowering, I harvest the same robust plants 2-4 times within a season.

I have observed and lightly harvested bright yellow curly gumweed flowers on plants growing out of cracks in the seaside rocks in Victoria, BC in mid-November.

I try to harvest the buds just prior to the opening of the marginal florets and the appearance of the first bright yellow petals. The buds are nearly spherical with flat tops; immediately prior to opening, suitable buds present a plump puddle of white viscous gum which may cover the entire bud top. This seems to act as a defense against herbivores and insects; an insect of some sort does manage to lay eggs under the bottoms of young floral buds prior to the appearance of any gum and ofttimes buds will have insect larvae and a lot of brown frass in the receptacles, subtending the actual flowers. I doubt if this detracts from therapeutic efficacy of such buds in extracts. It may enhance healing.

On hot days (over 80° F), the gum becomes much less viscous and often spills off the buds onto their leafy stalks. Rarely is there gum on the basal leaves, which may be withered or even absent in driest habitats, even though the plants are brightly flowering. The gum seeps into the opening bright yellow composite floral cluster, enabling pollinators to safely land without becoming mired in the sticky gum which starts to dry and harden as the blossom continues to grow and open. Although I pick mostly gum-puddled floral buds, I do pick a few immature hardgreen gumless buds and a few bright yellow open flowers for each batch of extract.

PROCESSING CURLY GUMWEED FLORAL BUDS

I use only freshly picked Grindelia floral buds for extracts. This means into the oil or aqueous alcohol as soon after picking as reasonable.

I have shipped and delivered fresh buds to customers, after carefully cooling the buds to prevent composting in transit. The rapidly developing buds are extremely exothermic and can heat up quickly in confinement. I pick into doubled paper grocery bags with handles and spread the buds by cutting open the bags and placing in shade or cooler if possible to cool them if I am harvesting several bags full of buds.

For drying, (for insistent customers) I place them on a 3’x 5’ sheet of ½ inch mesh hardware cloth screens near the ceilings of my drying rooms. The smell of drying curly gumweed buds fills the cabin and gladdens me. I do not use the dried buds, which can take 2-4 weeks to completely dry at 80-100° F, because I suspect therapeutically important components evaporate from the gums whilst dehydrating.

PREPARING MEDICINE FROM GRINDELIA

Grindelia Oil:

I use 1 part gumweed buds to 3 parts oil (olive oil) and macerate the buds loosely covered at 80-110° F for 2- 4 days. Then I let the buds and oil work at room temperature (usually hot summer days) for a month or so and decant off the oil. During maceration I stir the buds up into the oil at least once daily.

Grindelia Tincture:

Similar to the oil extract, I use 1 part buds to 3 parts aqueous alcohol (50-70%); the extracting container is always glass ? big jars, with tightly-fitting lids to conserve both alcohol and volatile gum components. (Because I have observed the gum to partially dry quickly after buds are harvested and when the gum is removed from the floral gum puddles, I know that a solvent of some sort is evaporating, rather than the gum hardening from exposure to air. This alleged volatile is not mentioned in constituent lists (Osol) because the material analyzed is probably dried. I place the macerating buds on the shelf above my wood heater (going all summer to dry the herbs and seaweeds) for up to a month and then leave the buds in the alcohol until the tincture is used. I am a firm believer in the continual rearrangement of all solutes in a polar solvent. This implies that the potential medicine is continually changing. YUP.

I have not yet made tea from fresh Grindelia buds.

Wined Grindelia Buds:

The wonderful odor of drying Grindelia buds reminded me of Retsina, the resin/gum-flavoured wine of Greece. (Which is probably flavored with resin from the Styrax bush).

I eventually (over 20 years ago) put about a pound of fresh Grindelia buds directly into a 1.5 litre bottle of bargain chenin blanc white wine (obviously after removing 1 pint of wine), recapped the bottle and shook it daily for a month or so. Delicious ersatz Retsina without the freight cost or import duty resulted. I have determined over the decades that higher quality white wine with Grindelia buds produces a more drinkble homemade retsina.

Honeyed Grindelia Buds:

Fresh Grindelia buds are put in warm (80-90° F) honey - one part buds to 2 parts honey - for months. The honeyed buds are useful alone for sore throats and chronic asthma. Mixed with honeyed Osha roots and honeyed Elecampagne roots, the combination forms a very soothing throat medicine.

THERAPEUTIC USES OF GRINDELIA BUDS

The most fabled use of curly gumweed extracts is as a topical wash in alcohol, or as a lotion in alcohol and/or oil for relief from Rhus (poison ivy, poison oak) dermatitis lesions, applied liberally and frequently. I have not used the plant thusly.

I have no clear sources indicating indigenous use of Grindelia for Rhus lesions.

My uses have been for a mildly calming sensation from the tinctures or ersatz retsinas and for flavoring bitter cough syrups, and tincture mixes for all bronchial distresses, particularly bronchial spasm, chronic and acute asthma, dry coughs, suspected whooping cough, and as a reliable expectorant.

There is a claim (Felter) that cystitis/bladder and urethral infections can be quelled with Grindelia tincture or tea. I have not used it thus.

With colds, coughs, flu, I use 5 drops tincture under the tongue or in strong hot steeped yarrow tea. With a good strong, well-extracted Grindelia bud tincture, a few drops of the tincture into herbal tea will yield a cloudy precipitate of gum constituents.

I have used the combined tinctures of Grindelia buds, Osha root, Elecampagne root, and yarrow for especially sore throats and suspected Chlamydia pneumoniae.

M. Moore suggests that Grindelia is called “gumweed” because it can be chewed like chicle. Hmmmmm. I wonder if he ever tried to chew a few gumweed buds?

He states that the flowers and leaves can be used interchangeably for tea and honey for sore throat, bronchitis, and when an expextorant is needed.

The Eclectics (Felter) used Grindelia externally to promote skin regrowth and to heal reluctant, persistent ulcers. The leaves have been smoked with Stramonium to relieve paroxysms of spasmodic asthma. The tincture is especially for asthmatic breathing with chest pains and subacute and chronic bronchitis in old persons, and for bronchorrea and emphysema.

REFERENCES

Bianchini,

F. & Corbetta, F. 1977. Healing Plants of the World. Pp 96-97

Felter, H.W. 1922. The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology, and Therapeutics.

Pp 397-98.

Moore, M. 1979. Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West. Pp 80-82.

Osol, A. et al. 1947. Dispensatory of the USA. Pp 1454-5.

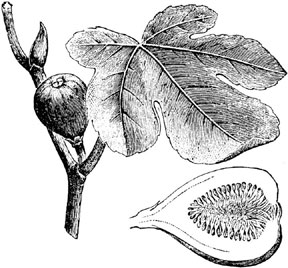

FIG LEAVES (Ficus Carica)

Edible

figs have been cultivated for thousands of years (Grieve). The many varieties

are cultivated commercially and privately in every suitable habitat. They

are prized for their hardiness, drought tolerance, exquisite sweetness (up

to 50% dextrose in fresh figs, 70% in dried figs; simple sugars were very

important medicines in earlier times), obvious contributions to robust health,

and long storage life when dried.

Edible

figs have been cultivated for thousands of years (Grieve). The many varieties

are cultivated commercially and privately in every suitable habitat. They

are prized for their hardiness, drought tolerance, exquisite sweetness (up

to 50% dextrose in fresh figs, 70% in dried figs; simple sugars were very

important medicines in earlier times), obvious contributions to robust health,

and long storage life when dried.

Maria Reich (author of Mystery in the Desert, a tri-lingual, German, Spanish, and English account) predominant researcher of the lines and figures in the desert near Nazca, Peru for over 50 years, claimed to my students and I during a working visit to Nazca in 1972, that figs were the perfect food and comprised at least 50% of her daily diet. Sixty-nine then, she continued strenuous work into her mid-nineties.

Immigrants, primarily from the Mediterranean countries, introduced edible figs to both North and South Americas. There were no commercial fig plantations in the United States until after the successful introduction of Date Palms to the Indio area of Southern California. After that, attempts were made to grow figs in large plantations. The trees thrived, fruit buds formed, and withered and dropped with little or no mature fig production. This was extremely disheartening.

After several frustrating years, to help solve the problem, two agriculture students from UC Riverside were sent to Mediterranean fig orchards to see how fig culture was practiced there. They observed that each spring fig growers brought many branches of the local wild figs (F. caprificus) into the orchards and tied the branches to the cultivated figs. Then the growers, their families, workers, neighbors, and others built huge bonfires, played music, drank lots of wine and let nature take its course. The students returned and waxed eloquent about all of it except the wild fig branches.

Astute professors suspected the students were inadvertently omitting some critical information, since mere partying did not seem in itself a serious agricultural practice. Of course, the wild fig branches contained copious eggs of the wild fig wasp (Blastophaga glossorum) which pollinates fig flowers by crawling into the hollow receptacle to feed, taking pollen to the pistillate flowers further within.

The fig is the most peculiar flowering plant in that the so-called fruit is actually a receptacle turned inside out, with the flowers inside.

Once the wild fig wasps were successfully introduced to the California Fig plantations, figs were abundantly produced.

Eventually fig varieties were discovered which produced figs without the assistance of the fig wasps. (I grow such a delicious variety my self at 49° N. It is a variety from the Ukraine.)

After several years of fig harvests by migrant workers, health workers reported an epidemic of Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease). The overt symptoms of tissue erosion, particularly finger tips, webbing between fingers, earlobes, nostrils and other places were obviously leprosy (which seems to be increasing in the United States in the past 20 years). Eventually, the alleged symptoms of “Leprosy” were determined to be lesions caused by prolonged contact with the juices of pruned fig branches and picked figs. The active eroder was analyzed to be phenol, a known tissue solvent. Osol writes: “ the unripe fig yields an irritant juice which inflames the skin and may even disorganise it”.

Protective clothing was provided for the harvesters and the ulcerous lesions no longer occurred.

When the leaves, fruit buds, or growing branch tips of edible figs are broken, abundant latex oozes out in viscous opaque white drops. This latex is produced and stored in long specialized cells called lacticifers (similar lacticifers occur in dandelions, and most other latex-producing plants). On exposure to air, the latex dries and polymerizes to a variant of crude rubber (rubber trees are in the same family as figs). This latex is not only unpleasant for herbivores, it also quickly seals fig plant wounds, reducing the need for the fig to grow new tissue to close wounds immediately.

The latex interiors of lacticifer cells are inhabited by complexes of strange motile protozoa which contain latex-eating internal symbiotic bacteria in special housing organelles. There are hundreds of different lacticifer obligate protozoa. They are spread from plant to plant by piercing insects which feed on the latex .

Fig Leaf Salve

Fig leaf salve is easily prepared by mixing one part of finely cut (a knife is recommended rather than a motorized chopper, because of the latex problem) fresh, young green fig leaves with three parts of a suitable oil. These days I use organic olive oil.

My teacher, Ella Birzneck, preferred Bear Fat when she could get it, and then goose fat, schmaltz, lard in descending order of preference. How did she, a non-hunter get bear fat? When she was homesteading and the local healer in the bush of Manitoba, she would be given bear and other game animal fat in trade for her medical help, including midwifery. I was able to obtain bear fat from taxidermists who prepared bear skins. The taxidermists were very glad to get rid of bear fat because it attracted rats and there was so much of it. I learned that it goes rancid very quickly unless frozen or mixed with lots of poplar bud or chaparral oil.

The oil and chopped fig leaves are placed in a double boiler and heated to 120-140° F for 12-24 hours. I use a candy thermometer to determine temperature; I also use a dedicated salve crockpot when AC current outlets are available.

After heating, the mixture is allowed to cool to body temperature and strained to remove the fig leaf pieces. In the last decade, I have been adding a dozen or so chopped, hard unripe green figs, at the suggestion of the herbalist, Rani Lynn, who observed the lush latex droplets oozing from them.

THERAPEUTIC USES OF FIGS

Therapeutically figs were prized as a reliable laxtive (Grieve, Osol, and PDR for Herbal Medicines 1998). The PDR claims, “Figs: Medicinal Parts: Fruit and Latex. Effects: no information available. Fig preparations are used as a laxative. The claimed efficacy has not been sufficiently documented. Dried figs were roasted and ground for a sweet refreshing beverage. Fig latex was used on warts and to prepare a topical oil for skin problems.” Ella Birzneck cautioned that fig leaf salve works for everything except ringworm, for which she used coal oil or kerosene topically.

“Fig tree latex was observed to inhibit growth of transplanted sarcomas in rats when latex fractions were injected subcutaneously or intravenously.” (Osol) This is not recommended at home.

Ear Lobe Lump Resolution

An agitated fellow stopped me whilst I was walking on the only road and asked if I could look at his ear. I made a lame joke about reading his mind and agreed. On the outer rim of one ear only, was a large protruding ovoid mass. I inquired if I could please examine it more closely and manipulate it a bit. OK. There was no inflammation (redness, swelling, heat), no sign of foreign embedded material, no broken skin, it was insensitive to vigorous pinch, and barely attached to the ear cartilage. It allegedly had been steadily enlarging painlessly for several months. The fellow wondered if I could help remove the lump using some of my herbal “stuff,” so he could avoid surgery or even a biopsy. Without hesitation I said “ Of course!” This was opportunity. Compliance was my only concern.

I told him I would prepare a topical medicine which would shrink and disappear the lump. I asked for a few days to prepare the salve.

I immediately went home and harvested fresh vibrant young green fig leaves (I have observed that older, somewhat even slightly-yellowed fig leaves are not as efficacious as the younger ones), and a dozen little hard, green, unripe figs, chopped them well, and macerated as above in hot olive oil. I also harvested several 2-year old Greater Celandine roots (Cheledonium majus) with abundant red latex, cut them into small pieces and prepared a separate 1:3 oil extract in hot olive oil(120-140° F). After a few days, the oils were strained and combined, and solidified with beeswax and cocoa butter. I gave a pint of salve to Dennis with fierce instructions to apply every day, keeping the lump and adjacent area well-covered always, if possible. I stressed that compliance was critical and that the lump would be gone before he had used all of the salve. It was, after several months, leaving a persistent concavity in his ear rim.

My reasoning was: combine the known tissue erosive property of fig sap with the known anti-mitotic action of celandine root sap. No complications.

Fig Salve Apparent Failure

A 50% fig leaf oil salve was not effective in resolving a persistent case of presumed Lichen Planus.

REFERENCES

Grieve,

M. 1931. A Modern Herbal.v.1: Pp311-313.

Osol, A. et al. 1947. Dispensatory of the United States. Pp.1454-5.

Physicians’ Desk Reference for Herbal Medicines. 1998. Pp. 848

About Ryan | Articles | Contact Ryan

©2005-2021 Ryan Drum

P O Box 25, Waldron, WA 98297-0025

Updated 04-10-2021

Website by